Per copyright laws this article has been republished verbatim with attribution from its original source or internet link, which may or may not be active. For the most recent and accurate information, please use our Visit/Contact Us link.

The Chieftain Toccoa, Georgia Tuesday, September 5, 1989

By: ANGIE RAMAGE Special to the Chieftain

Just like most areas, Toccoa Falls has its myths and its history.

Some of the tales we hear come from well meaning old-timers who have lived through a noteworthy era of time.

Other stories are simply passed down generation by generation through moms and dads to wide-eyed children at bedtime.

One particular tale has captivated my attention over and over again — so much so that I began to research the individual involved and found a beehive of information.

I won’t lay claim to the details surrounding the story. I do know that the subject of my research did exist, and that he made his home in Stephens County part of which is now Toccoa Falls College~

So history buffs get ready — this one’s for you. On the other side of a small lake, three individuals moved through a clearing. Their footsteps are periodically interrupted by the pushing of low-lying brush out of the way. It was mid-June and sweat ran down their faces.

From time to time the travelers stopped to remove invading ticks from pant legs as their shadowing journey continued.

Finally, the search ended under two leggy pine trees. “This is the spot!” called the older man to his two younger companions. Hurriedly, the three began to clear away the years of undergrowth beneath the pine trees. A lone grave marked by two odd shaped stones peered up at them, and for several seconds the only sound that was heard was that of a small hawk as he stretched out his wings in flight across the pond area.

“We are here,” said Leon Gathany, bending over the grave. “I haven’t been here since the late 60s, and who knows what lies beneath these stones.”

Like children caught in a fascinating tale, their minds studied their surroundings and wondered what life would have been like here in these backwoods in the early 18OOs.

Gathany’s word finally broke the silence. The house is near here up on the ridge,” he said.

The three began to move back toward what once was the old post road.

There they separated and while remaining in eyesight of each other, they continued the search. Again it was Gathany who found the treasure. The foundation of the house was still visible after more than 150 years. Together they stood near the remains of what was a crepe myrtle tree — “A sure sign of an old home place,” says Gathany.

“A true mystery,” said one of his younger cohorts.

“Yes,” said Gathany. “He was 95 when he died and was buried alone.”

“But how did he get to this area and why?” they wondered.

Col. William Wofford, Revolutionary War hero and American patriot, was born on Oct. 5, 1728 in Maryland. He was among some of the first known white settlers in what is now Habersham and Stephens counties.

He and his relatives and friends settled on Nancytown Creek and Wofford’s Creek as early as 1783. Wofford Creek feeds Nancytown Lake which lies next to Lake Russell near Mt. Airy.

When the line between the state of Georgia and the Cherokee nation was surveyed by Benjamin Hawkins, a U.S. Indian agent, in 1797, it was discovered that the Wofford settlement was located just over the boundary on Indian land. This generally was the original north boundary of Franklin County from which Stephens County was later formed.

Since the US government felt that Wofford had “ignorantly” placed the settlement with the Indian Nation, they did not ask him to move from the land. Wofford petitioned for a cession from the Cherokees to include this land in Georgia, and the government went along with this plan. A treaty was established on Oct. 31, 1804, for a tract of land that ran 23 miles and 64 chains in length and four miles wide.

However in 1811, J. Meigs wrote to the Secretary of War stating that the treaty was never ratified by Congress. The Indians did this so no mistake would be made by the white man in the future. Later reports from the state department show that the treaty of cession was mislaid for nearly 20 years, and was not ratified until 1824 by the United States.

William’s father, Absalom Wofford, had moved to America from England and settled in Pennsylvania. He had five sons and among these were William — who became a man of “great enterprise.”

Wiliiam Wofford built a noted ironworks at Lawson pork on the Pacolet River in Spartanburg, S.C., and was one of the leading citizens of the area. He served as colonel in Williamson’s Cherokee Campaign in 1776. Later in 1781, Wofford saw his ironworks destroyed by “Bloody Bill” Cunningham during a raid that is still noted in the gages of Revolutionary War history.

“A leading patriot” is the title give Wofford by today’s historians. While fleeing from North Carolina to Georgia in 1779, he was linked to the likes of Lt. Col. John Moore.

Wofford and Moore were part of a group that pursued the Tory party in the Battle of Stono Ferry. It is often noted that both Georgia and South Carolina suffered great persecution at the hands of the Tories.

It was after this particular campaign that Wofford sold what remained of his ironworks to a man named Simon Berwick.

He, along with his family and other friends, moved to Turkey Cove on the Catawba River in North Carolina where he purchased 900 acres of land and built a fort and grit mill. There was safety in the shelter of this man’s shadow, and the settlements he established grew under his watchful eye.

After the Revolutionary War Col. Wofford moved to Franklin County at which time took in the counties that are now Stephens and Habersham, as well as several counties in South Carolina.

According to Mrs. Lillie Isbell, in her book on the Wofford family, the Wofford settlement was squeezed out of Franklin County during the original survey. She writes, “Wofford was a man without a country.”

It was true after all his service to the country1 Wofford did feel “put out” by his exclusion from the surveyed land.

Legend has it that he mounted his horse and rode to Washington to talk with authorities about his land holdings in Georgia. Because of Wofford’s credibility, the United States agreed to pay the Cherokee Indians $5,000 and $10,300 per annum for the property rights. Eventually Wofford would own close to 2,000 acres of land around Toccoa, including what was then called the “High Falls” to the middle fork of the Broad River. Wofford was the progenitor of the Wofford family in Georgia. Family tradition says his son, Nathaniel, was the first white child born in this area.

Other grants of land were acquired by Wofford over the years according to records made by John Gorham, who surveyed close to 1,000 acres of land for the colonel. He was married three times. His first wife, Sarah Camero, died in 1772 and is buried in Spartanburg, SC. Little is known about his second wife, Nancy Greenleaf, though records show that she married Wofford in 1773.

Mary Bobo was his third wife who died the same year as Wofford, in 1820. The National Archives has deeds with Mary’s “X mark on them from 1790 and 1794 concerning her husband’s will. Though he married three times, all of Wofford’s known children were by his first wife, Sarah.

His seven children who later became heirs to the Wofford estate were Mary Wetherspoon, Ann Clark who after the death of her first husband married William Bright, Benjamin Wofford, Nathaniel Wofford, Charlotte Baker, Sarah Gilespie and James Wofford.

The original abstract of title for the land around Toccoa Fall shows William Wofford as its third owner behind Coy. James Irwin and Joshua Catcher.

The Toccoa tract of land, including the falls, was said to him on Aug. 23, 1817 — only three years before his death.

The Toccoa Falls property changed hands 23 more times before it fell into the hands of E.P. Simpson in 1898. Names listed in the deed throughout the years include such entries as the Bakers, the Jarretts, the Dooleys, the Mathews, and the Haddocks.

The land was first separated and broken down through family heirs. Later it was sold and purchased through land deals until it became the property of Dr.R.A. Forrest in 1911. Today it is the home of Toccoa Falls College.

Mary Wofford died shortly before her husband but records of her actual place of burial have not been discovered.

Records at the Georgia Archives in Atlanta do show that Wofford is buried near Toccoa Falls. James Puckett Jr., the past chairman of the Revolutionary Graves Committee S.A.R., wrote in 1966 that “Wofford is buried on the campus of Toccoa Falls College in Stephens County1 Georgia.”

Puckett later determined the location of the gravesite, as well as the home site, through long hours of research in which land deeds and maps of the area were used to paint a final picture of the Wofford saga. The first census of Habersham County in 1820 shows Col. Wofford living alone near the falls with three young slaves.

“So no one knows what his last years were really like?” asks one of Gathany’s companions.

“No. not really. He died when he was 95 and was alone except for his servants,” said Gathany as he stirred the leaves that covered the only remaining evidence of Col. William Wofford’s life.

The rock foundation of the house was still evident even at a distance.

Gathany bent over and picked up a large stone that was burnt orange in color.

“I wish these stones could talk they would tell us all we need to know. See the color of this one? When a rock is this color it usually means there was a fire,” he said.

“I wonder if his house burned right after his death or if vandals burned it much later?”

“No way to know that today but maybe later after some research,” concludes Gathany.

In turning to go, they all found themselves talking at once about this man, Wofford.

“I’ll bet he was a brave soldier,” said one. “Yes, he would have to be — well, just think he was one of our first white settlers,” said another. “And from what I understand some of his sons followed in his footsteps and became soldiers also.”

“All fighting for freedom and their rights as American citizens,”

I wonder what he thought of this land, this country.” There was a pause as the three looked out over the ridge at the tall hardwoods and the young energetic pines.

What of Toccoa?”

“That’s Toccoa — the Indian word for beautiful.” There was a smile, then came the reply. “Well, beautiful, of course.”

Originally published at: http://www.lrwma.com/historicaldocs/wofford/soldiercametostay.htm

Update on Wofford grave site: Recently Professor David Jalovick of Toccoa Falls College was instrumental in cleaning up and documenting the William Wofford gravesite up Deadman’s Branch at Toccoa Falls College. The picture is of the group who volunteered to work on the site.

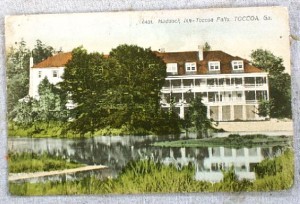

I’m curious as to when the Haddock Inn was owned by William Haddock. He’s my 4th great grandfather and I’m told his brother Isaac is the one who built Haddock Inn. I’d like to find out who William sold it to and if Isaac sold it to William. How would I go about finding this information?

Thanks in advance

Thank you! Pretty cool to hear about my great great great great great great great great grandpas story.

Thanks so much for catching this story before becoming a dead link. It had so much information that will be useful in educating others.

What an interesting story. I always wondered about the origin of Toccoa.